As WWII came to a close, the United States faced new obstacles. With the impending return of over fifteen million Americans, a plan for postwar recovery was vital. Twenty-five years earlier, after the First World War, insufficient government planning would contribute to the Great Depression and lead to the Bonus Army Conflict. In an effort to avoid falling back into an economic depression, government leaders passed the Servicemen’s Readjustment Act of 1944. The law, which passed by one vote, would become the single greatest reform in American higher education.

Events Leading to the Servicemen’s Readjustment Act of 1944:

Following World War I, the United States neglected many of its veterans; who, in return for their service, were promised financial compensation. In 1925, Congress voted to give them $1.00 for each day served stateside, up to a maximum of $500, and $1.25 for each day served overseas, up to $625. However, the newly passed legislation came with a catch; bonuses wouldn’t be paid in full until 1945. Before then, veterans were permitted to borrow up to 22.5% of their bonuses, and in 1931, congress voted to increase the amount to 50%. Despite the increase, demands for full bonus payments intensified as the Great Depression worsened. The following year thousands of veterans from across the nation, led by former Army sergeant, Walter Waters, descended on Washington D.C. The protestors, known as the Bonus Army, setup an elaborate camp in Anacostia Flats.

By the end of June, the situation would reach a tipping point. Eleven days after Senate voted against the Bonus Bill, President Hoover ordered General Douglas MacArthur and the 12th Infantry Regiment to clear out Bonus Army encampments in Washington. By late afternoon they reached the Anacostia Flats; after giving protestors twenty minutes to evacuate camp, MacArthur ordered his men to burn it down. In the end, a few lay dead; current data suggests there were anywhere between 50 and 100 casualties in total. In the weeks following the attack, stories and images of the army attacking its civilians spread across the nation. Four months later President Hoover lost his bid for reelection to Democrat Franklin D. Roosevelt.

Bonus Army Conflict: Important Locations – Washington D.C.

The Bill:

World War II gave the economy a much-needed boost; it provided jobs for millions of Americans, both at home and abroad. By 1944, an allied victory appeared increasingly likely, and the nations goals began to shift. For President Roosevelt, the postwar effort had two primary objectives: “first, how to adjust wartime production into peacetime economy, and second, how to avert the civil strife of disgruntled military veterans who arrived home without jobs or good prospects” (Thelin, pp 262). Just a decade earlier, Roosevelt won the presidency on the heels of a national crisis caused by the federal governments inadequate care of its WWI veterans. He understood the importance of taking care of America’s veterans.

Throughout the first half of 1944 Congress worked on developing a bill that met President Roosevelt’s expectations. Initially the main idea behind the bill was to reintegrate veterans into the workforce over the period of one year. During that time, every veteran was eligible to receive $20 of weekly unemployment. However, through the influence of several lawmakers, educational benefits were incorporated into the bill. On June 22, 1944, in a joint conference, the Servicemen’s Readjustment Act of 1944 passed by just one vote. The law, also known as the G.I. Bill, guaranteed “a year of education for 90 days’ service, plus one month for each month of active duty, for a maximum of 48 months” (Keister, pp 128). It paid academic costs, including tuition, books and supplies, of up to $500 per year. Additionally, they were allocated a monthly living allowance; $50 for single veterans and $75 for married veterans (Thelin, pp 262).

Impact of the G.I. Bill of Rights:

From the beginning expectations for the bill were low. People thought returning soldiers were more likely to enter the workforce than go to college. In the summer of 1945, the most optimistic expectations estimated that less than 10% of veterans would use the bill’s educational benefits. According to A History of American Higher Education, during the fall of 1945, eighty-eight thousand veterans had already been approved for participation. One year later, the number multiplied more than ten-times, surpassing one million participants. The G.I. Bill changed the nature of higher education in a way that was unprecedented (Scimecca, 2012). It was available to every veteran who met the eligibility requirements (which mostly dealt with time in service); there was no limit on the amount of people who could use it. Additionally, it could be used at the institution of his or her choice as long as the government recognized it. The G.I. Bill of Rights became the most significant piece of legislation for the improvement of higher education in America.

Prior to World War II, higher education was seen as a privilege reserved for the rich. College was expensive; outside of a scholarship there was very little chance for working-class families to afford it. With the creation of the G.I. Bill, young adults who previously would have never dreamed of going to college were encouraged to do so. The G.I. Bill was pivotal in the emergence of the American middle-class. Many of those who used their benefits were first generation college students. Generally they recognized the values and importance of an education; in turn, they would instill the same values in their children. Besides education, the Servicemen’s Readjustment Act provided financial benefits such as low interest mortgages for homes and businesses. “Loans helped give momentum to an already-booming housing market. By 1956, the rate of homeownership was 60 percent, up from a prewar level of 44 percent” (Leddy, 2009).

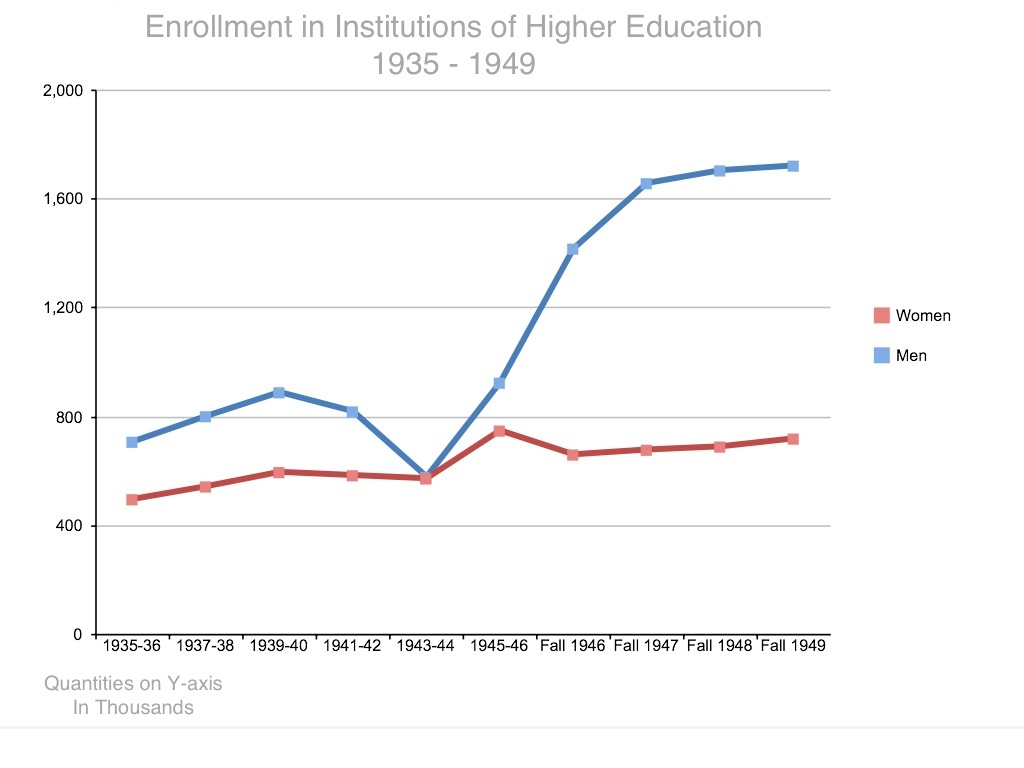

By the time the benefits of the initial bill ended, it is estimated that over 50% of World War II veterans used their educational or educational-training benefits (Mettler, 2012). During the 1920’s, enrollment in higher education between 18-24 year olds increased by about .5% every year. Surprisingly during the Great Depression, enrollment remained steady every year except one; from 1933-34 there was a .7% drop (National Center for Education Statistics, pp 77). One possibly reason for this: many people in the upper class remained unaffected by the economic decline; they continued sending their children to college. From 1941-42, when America began entered the war, college enrollment dropped from 9.1% to 8.4%; the following year it dropped 1.6%. During these years enrollment was down in both men and women (NCES, pp. 77).

In the first academic year after World War II enrollment rates (18-24 age group) jumped from 6.8% to 10%. By 1949, 15.2% of 18-24 year olds were registered in higher education. There is no doubt the rapid, postwar increase is attributed to the Servicemen’s Readjustment Act of 1944.

It is important to note that the G.I. Bill, despite its advertised all-inclusiveness, was much less accessible for many African Americans and women. In the South, Jim Crow laws were still prevalent, making it difficult for black servicemen to attend a large number of institutions. In the five years following the war, enrollment among women increased only slightly. In fact only 2.9% of eligible women took advantage of the bill. The reasons for this are twofold: first, it wasn’t until the 1970’s that it was culturally acceptable for women to go to school, and second, most women had no idea they were eligible to use the bill.

The Servicemen’s Readjustment Act of 1944 was an enormous success. In addition to reintegrating the veterans of World War II into society, it created a foundation for the economic boom of the 1950’s. Prior to their return, generous estimates predicted that only 8-10% of veterans would use their benefits. However, by the time the bill expired, over 51% of eligible veterans used it for education. Despite having a few drawbacks, which were really more a result of the era, the bill was a huge success. Since it expired in the 1950’s, a number of similar “G.I. Bill’s” have been passed; in fact it is still in use today.